A few weeks ago I visited Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, my hometown and current home to my parents and siblings and many good friends, including one very important friend named Jackie who recently moved back to PA with her husband and son (my adorable godson!) after some years in Oregon.

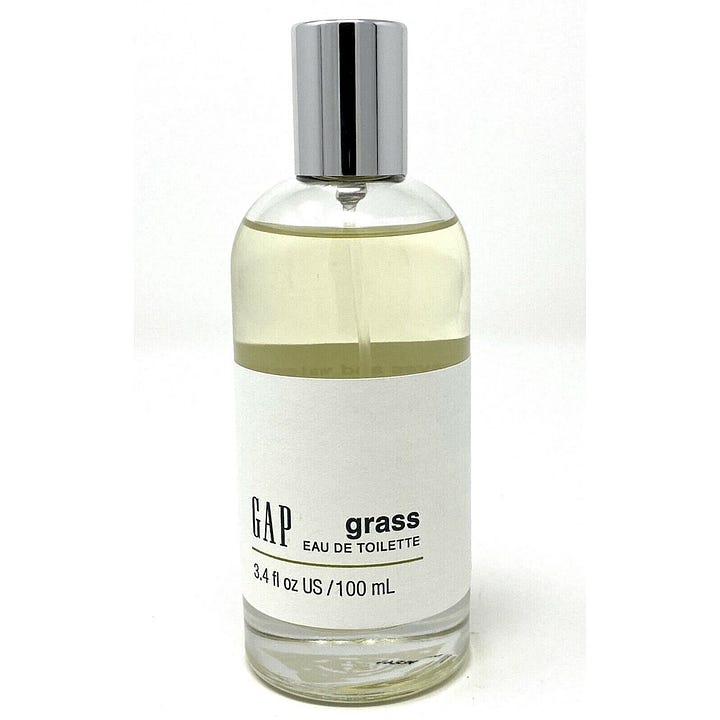

I showed up at Jackie’s apartment and she offered me a few spritzes of Gap Grass. The original was launched in 1994, and we both agreed that this reformulated version doesn’t smell the same as it did when we were teenagers. It’s difficult for me to say with confidence what exactly is different about it — accurately describing a smell from memory is hard — but it’s definitely weaker and more generically ‘90s, only gesturing at the chemical “fresh mowed” grassiness of the original.

The Gap scents of that era were all more or less in the same family of inoffensively fresh, pseudo-natural climate controlled green (or maybe pink floral), mall scents, but each had some distinct quality, some slightly sharp edge or surprising personality.1 A recent visit to my local Gap outlet store revealed that these scents are now barely distinguishable from one another. They remind me of being a teenager but only in that vaguely familiar but ultimately foreign way that encountering an actual teenager reminds me of being a teenager. It’s the olfactory version of That '90s Show.

In a piece on Norwegian artist and chemist Sissel Tolaas, Shruti Ravindran explains, “Smell isn’t like most other senses. Unlike sight or hearing, olfaction is immersive — a subliminal contact sport.” Scents, for better or worse, are “directly conveyed to the part of our brain that processes memory, which is why odors prompt such immediate responses.” In other words, as evocative as a song, or the feeling of a certain fabric might be, scent memory is more reliable and more specific than the memory linked to other sense. It rarely misremembers.

But it’s more intense than that. Smell trips emotional synapses, Tolaas says, triggering both a picture of a moment in time and the visceral feeling of being in that moment. This is why reformulated fragrances are often so deeply disappointing.

Anyway I, in turn, anointed Jackie with my purse spray of Demeter’s Tomato, which I’d packed because I knew the weather would be hot, and it’s a scent that unfailingly sends me back to Pittsburgh. Demeter launched Tomato in 1996, when I was 12. The company specialized (and still does) in one-note, photorealistic scents and Tomato smells exactly like the oil left on your fingers after touching the leaves and stems of a tomato plant. That is to say, it is a spicy green scent, not a red scent (there’s no marinera here, but maybe Demeter will tackle that one day).

In the ‘90s, having no personal income aside from the odd babysitting gig, I couldn’t afford to buy any of the wide array of (moderately priced) Tomato products – cologne sprays, candles, etc. – but I did sniff them whenever I happened to be in the vicinity of Shadyside’s medium-fancy gift store Kards Unlimited (which is still there, and is still, last I checked, the city’s premier supplier of RBG ephemera).

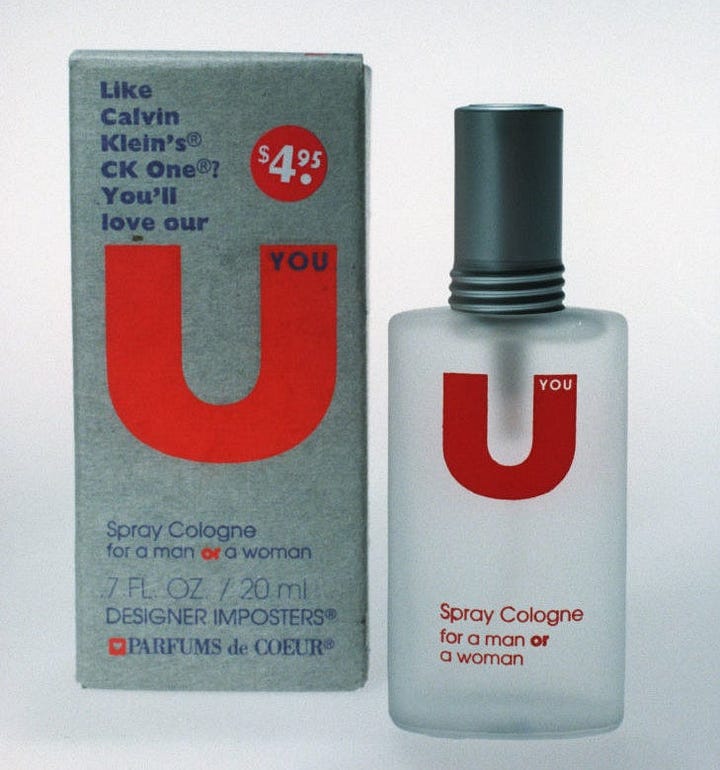

Instead I bought cheap, candy-scented body sprays and CK One fakes from KMart and Phar-More. I had a small aerosol of Gap Grass, of course, which I probably bought at the Monroeville Mall. I horded those precious spritzes.

In my later teens and early 20s I finally acquired a few Demeter scents: Graham Cracker, a basic vanilla with a slightly dry, slightly spicy edge; and (as a Christmas gift) Snow, which somewhat magically conveyed the metallic asphalt note you’ll sometime catch in a fresh snowfall. (One Fragrantica review describes the smell as “laundry detergent, stale clothes, and pungent ozone tang,” which sounds pretty cool IMO).

What is powerful about Tomato and Graham Cracker and Snow and much (if not all) of the Demeter line is that they are immediately referential. I was drawn to them to begin with because they triggered those existing scent memories of childhood, the neighbor’s vegetable garden (my sister, as I recall, liked to pick the tomatoes and throw them at cars); of Sunday school snack time; of dragging a sled up the hill at cold, gray twilight. And then those associations double back on themselves: Rubbing a tomato leaf with my fingers moves me through time to Kards Unlimited in the 90s, and then to Jackie’s place in April, and to all the other places I’ve been since finally buying myself a big bottle of Tomato, which smells just as it always has.

Tolaas has long been obsessed with this invisible world. “For me the sense of smell is being alive,” she says. When she wants to remember something, instead of taking a picture, she has a device that vacuums up the scent molecules. She is able to recreate and archive these various “non-obvious” scents (think sour milk, overripe banana and dirty rag) in tiny bottles. For her, every smell is important and serves a purpose, even the “bad” ones.

Demeter feels a bit gimmicky at times, but it turns out that their values are in line with Tolaas’s. In the description for Mildew, an employee recounts a conversation with a customer.

“Finally I asked her what aroma she really enjoyed. She said 'You know it's the smell of first turning my air conditioners [on] in May'. And I replied: 'Well that's Mildew'. We did Mildew in honor of her. And sent her some, much to her happy surprise.”

The reviews are mixed: Most complain that the scent isn’t mildewy enough, that it doesn’t match their memory. But one woman writes that she’s reminded of the way her Barbies used to smell after playing with them in the pool. “Not completely Mildew-y, but pretty close.”

Personally, I’m dying to get my hands on a bottle.

Is this an idealized memory? Perhaps.