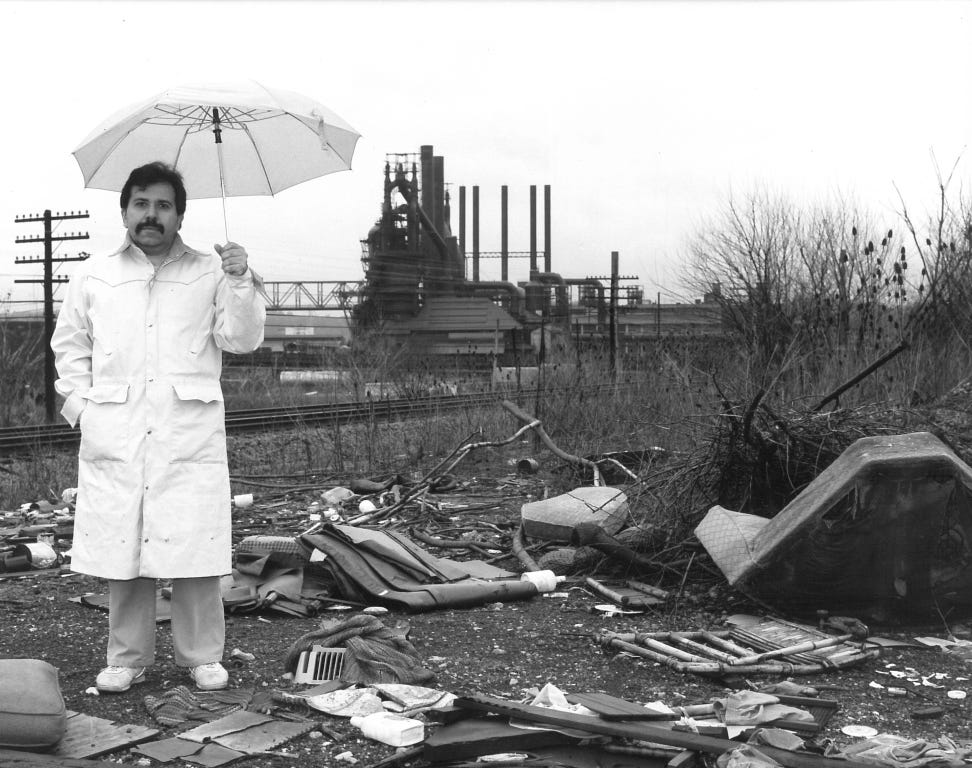

Tony Buba on Lightning Over Braddock

“I wanted to do a movie where the audience would get pissed-off at the filmmaker.”

Inspired by Werner Herzog’s recent New Yorker essay about his time living in Pittsburgh, I’ve pulled up something from the archives, a piece about Braddock, PA filmmaker Tony Buba. I wrote it in 2020 when Kino Lorber released a collection of Buba’s films, newly restored, on Blu-Ray. I originally wrote it for the Pittsburgh Current, which is no longer available to read online.

When Herzog caught a screening of Buba’s Sweet Sal in Pittsburgh in 1979, he asked to see everything else the filmmaker had made. By then Buba had already won a number of awards and a fair amount of national recognition, but Herzog’s advocacy didn’t hurt, and over the decades Buba’s films have been screened at major museums and festivals all over the world.

I’m posting this as it was first published but of course some things have changed: Summer Lee is a congresswoman and John Fetterman is a senator, and I trust that Buba is no longer 77. I will also note that I neglected to emphasis the importance of one of Buba’s primary collaborators, composer and performer Stephen Pellegrino. His musical numbers in Lightning Over Braddock are unforgettable.

Between 1980 and 1988 — the year Tony Buba released his feature film Lightning Over Braddock — more than 12 million American steelworkers lost their jobs due to plant closures. Twenty-five thousand of those workers lived along the 20-mile stretch of the Mon Valley. The town of Braddock, once known for its thriving business district, fell into a steep decline.

This is the backdrop of Lightning Over Braddock. But unlike Michael Moore’s Roger and Me, which came out the following year and is often mentioned in tandem, it’s not a straightforward documentary about the plight of the working class.

Lightning mixes interviews, protest footage, surreal fantasy sequences (including a steelworker-themed new-wave musical number), vignettes from Buba’s previous work, quasi-autobiographical meditations on fame or lack thereof, and a good-humored sprinkling of Catholic guilt. On the film-festival circuit Lightning bedeviled the organizers tasked with categorizing it. With each viewing it becomes less obvious where the documentation ends and the fiction begins.

In March, film distributor Kino Lorber released a newly-restored collection of Buba’s films on Blu-Ray; the two-disc set includes Lightning plus a couple-dozen shorts from the 1970s onward.

Buba, who is 77 and lives in Braddock Hills, spent the late ’60s and early ’70s in school, first studying psychology at Edinboro University, in Northwestern, Pa., and then film at Ohio University. When he’d return to his hometown to visit, “it was like when you don’t see your grandparents for a while, you realize how much they’ve aged,” he says. “That's what I saw with the town. The type of characters I knew were going to disappear.”

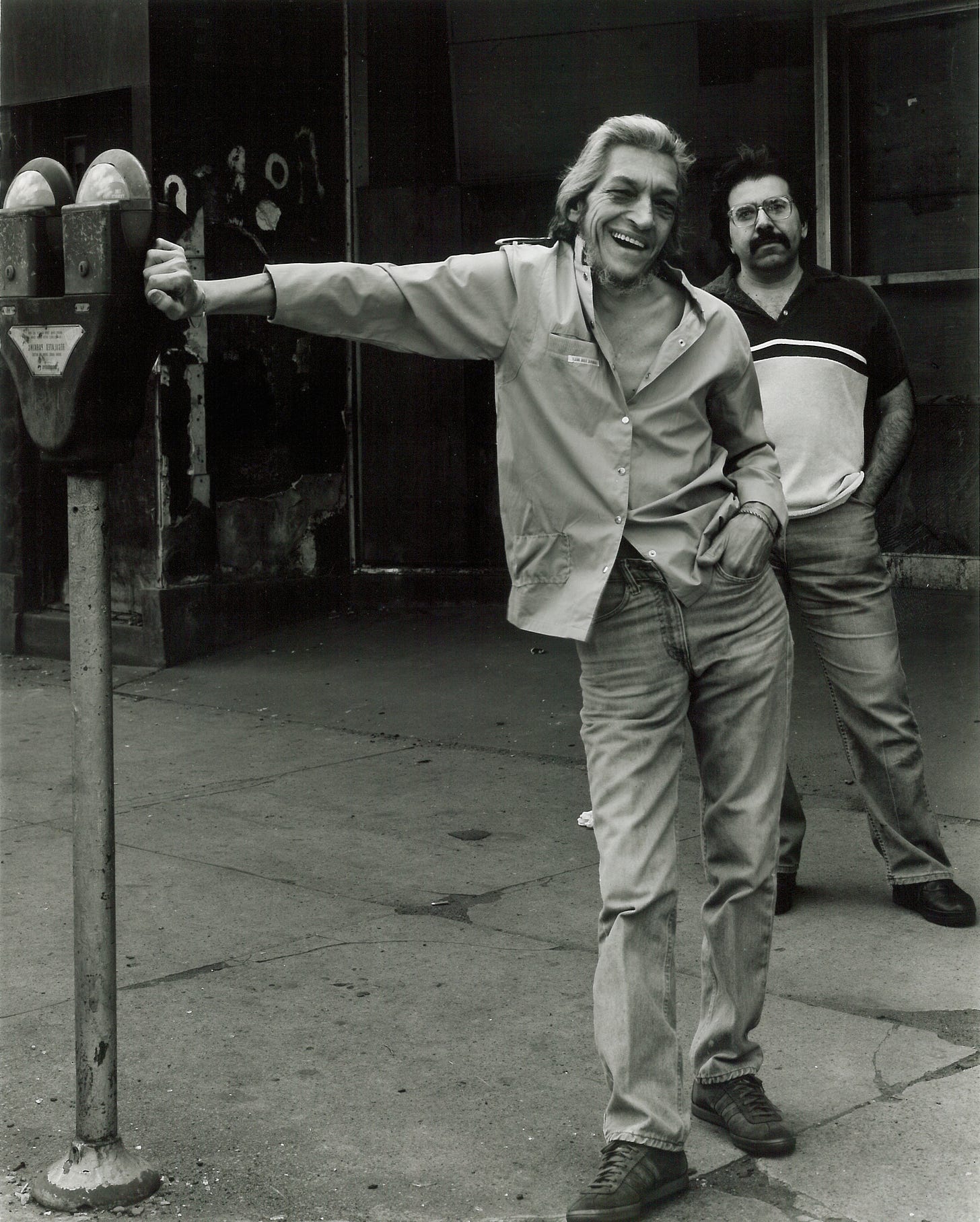

One of these characters was Sal Carulli, a skinny, trash-talking, wanna-be wise-guy with a cavernously lined face and wicked smile. In 1979 he was the subject of Buba’s short film Sweet Sal. That work, and others, attracted the notice of iconic filmmaker (and another champion of odd-balls) Werner Herzog.

This brush with mainstream recognition becomes a plot point in Lightning. Sal, thinking that it’s his acting abilities that captured Herzog’s fandom, turns on Buba and, in a series of vaguely threatening answering machine messages and under-the-breath mutterings, rages at him for stealing the spotlight.

“I wanted to play against that whole thing of the filmmaker having all the knowledge and sort of presenting it to the audience, being the voice of God, the superior,” Buba says. “I wanted to do [a movie] where the audience would get pissed-off at the filmmaker because all these steelworkers are losing their jobs, and he’s fooling around with this guy Sal. And the main issues are in the background.”

Buba knew that this unconventional approach would limit his reach. But Lightning Over Braddock found an audience in its own time, and was screened at major film festivals. It earned a nomination for Best First Feature Film by the Independent Spirit Awards.

Over the years Buba has shown his films all over the world, and has received a number of prestigious grants, including the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship. And every several years, Lightning — “This quirky film from the ’80s, or whatever they want to call it,” — gets rediscovered and Buba hits the road for more screenings.

Film critic Nick Pinkerton, who joined Buba on the director’s commentary for the Blu-Ray release, notes that — unlike contemporaries Peggy Ahwesh and Stan Brakhage, who were also working in Western Pennsylvania — Buba was not a hard-line experimental filmmaker.

Documentary filmmaking of that era had an eye turned to the destruction of working-class America, particularly in the Rust Belt. Buba was heavily invested in these themes too, of course. “But he [wasn’t] a particularly good fit with this documentary school at the time, in that he’s very very character oriented, there’s very little in the way of finger-wagging didacticism,” Pinkerton says. “The characters that he’s attracted to are not necessarily credits to society … but he likes hustlers, he likes small scale chislers.”

Pinkerton, who is originally from “Rust Belt adjacent” Cincinnati and lives in Brooklyn, likes to compare Buba to Harvey Pekar, the late author of the American Splendor comic book series. “Tony’s not self-presenting, in the film or in life, as a bohemian amidst the ruins of industry. He very much regards himself as a working-class guy who easily could have wound up on the factory floor, if indeed there was still a factory floor to wind up on.”

In other words, Buba — like his old friend George Romero — is nothing if not a regionalist. Despite their vastly different aesthetics, both directors stayed in the Pittsburgh area. Romero traveled when he needed to, but wanted to avoid the influence of Hollywood on his work. And while Buba always knew that moving to New York would likely have advanced his career, he admits, in Lightning, that he enjoys being a “big fish in a small city.”

Even so, there’s conflict between his role as a director of small, politically-conscious films, and a desire for a different kind of success. In one scene, he visits his priest to confess his most grievous sin. “Father, I no longer want to make social documentaries,” he says. “I want to make a Hollywood musical!”

Buba’s recent work remains Braddock-focused. Currently, he’s putting together a documentary about Pennsylvania State Representative Summer Lee’s campaign for reelection (Lee is a native of neighboring North Braddock). He’s also working on a project about his mother and grandmother, as well as something called Thunder Over Braddock. When we spoke in mid-April, he was using quarantine as an opportunity to sift through hard drives of old footage, in hopes of producing some small pieces. And he’s in the process of sending odds and ends from his collection to the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where his work is being archived.

“If you had asked me back then if [my work] was going to hold up for 40 years, I would have said no.” But as the failings and false promises of the free market become clearer every day, the anti-capitalist heart of Buba’s filmmaking remains resonant.

Braddock has, of course, enjoyed some good PR over the last decade or so, thanks in large part to efforts by the ambitious former mayor John Fetterman, who is now the state’s lieutenant governor. As with many other revitalization-ready locales, news outlets were eager to paint the struggling town as a haven for artists and entrepreneurs. But Buba understands the fuller story.

“You drive into Braddock, you get down to 5th Street and you have the Fettermans running the Free Store, and then you go to the end of the town and you have a restaurant where you can spend three or four hundred dollars on a dinner,” he observes. “Within that one-mile stretch it's the whole economy of the United States. All the disparities right there in one mile.”

Pinkerton puts it this way: “You can go in and start your own wine place, or your artisanal fromagerie, or whatever: You have the leeway to do that. But the fact remains, however many Etsy shops are set up in Braddock or Rochester, or in Detroit, it doesn’t go anywhere in replacing large industrial concerns that employed tens of thousands of people in the community.

“My feeling [is] that Tony, as a very dyed-in-the-wool blue-collar guy, has a very healthy dose of circumspection and cynicism about this.”

Part of the lasting appeal of Buba’s work is, Pinkerton reckons, that he's something of a canary in the coalmine. “The things that he’s particularly concerned with as they impact his home town are things that have been very much part of the dreaded ‘discourse’ over the past four or five years.”

At a time of intense generational tension and growing class conflict, not to mention mass unemployment, it's easy to forget that many members of Buba’s generation “got it in the neck very badly,” Pinkerton says. “The boomers that we think of as living through the sweet spot of history are not working class people.”

With that in mind, seeing Lightning in 2020 feels like a gentle challenge to look as closely at our communities and our neighbors as Buba has at his own for decades.

“Certain things that we’ve chosen to pay attention to over the last five years, the forgotten man that we’ve recently expressed some concern for,” Pinkerton says, “these are things that Tony has been paying attention to for a very long time.”