Last summer Leah McManigle saw Oneida play at a boardwalk bar in Rockaway, Queens. There were fans who had specifically come to see Oneida, but plenty of people had just wandered in looking to cap off their beach day with a beer.

McManigle watched the show from atop a picnic table at the back of the room. “The crowd was so into it,” she said. “Nobody went to get drinks, no one was talking, people were screaming and dancing and up on tables. The entire bar was packed and people on the boardwalk were stopping and like, Oh my God. They've been a band for 25 years,” she said, her voice slightly awed, “and they just did that.”

This was around the time that Oneida – who formed in Brooklyn in 1997– released their 16th full-length record, Success on Joyful Noise Recordings. The band was always characterized by power and stamina – in 2009, for example, they performed a 12-hour improvisational/collaborative piece at All Tomorrow's Parties – and Success is a true rock record: muscular, catchy, funny, sometimes slack, other times razor sharp. It’s a high-powered swirl of psych-rock, kraut-rock, experimental rock, punk rock, rock ’n’ roll-rock.

I interviewed drummer John “Kid Millions” Colpitts about the release, and McManigle in a separate conversation, the hook being that Oneida was celebrating the release in Pittsburgh with their friends Terry and the Cops, a band built, more or less, from the rubble of one of my all-time favorite bands, Rickety Records artists the Dirty Faces, for whom McManigle played drums.

My personal interest in Rickety in general and the Dirty Faces specifically has long bordered on the obsessive. Falling deeply in love with a so-called “local band” — a band to which you have consistent geographical access — can be as ecstatic an experience as any young romance. I came of bar-entrance age midway through their tenure, but when I did finally catch them one late night at Gooski’s I was spellbound. They were cool, they rocked, they were menacing in a way that can’t be faked. They had “it.” In my 2021 profile of Rickety for Bandcamp Daily you can tell there are still hearts in my eyes:

…while many aspire to rock ‘n’ roll debauchery, Dirty Faces were the real deal in terms of glamorized bad behavior. Each of the (then) six band members had a pseudonym, with [Terry] Carroll’s “T-Glitter” serving as a slightly less tyrannical Mark E. Smith-style bandleader. His lyrics, drawn from real-life legal troubles, drug adventures, sordid romances and post-9/11 dread, compounded the raw, psychedelic grit of the band’s loud and dirty sound.

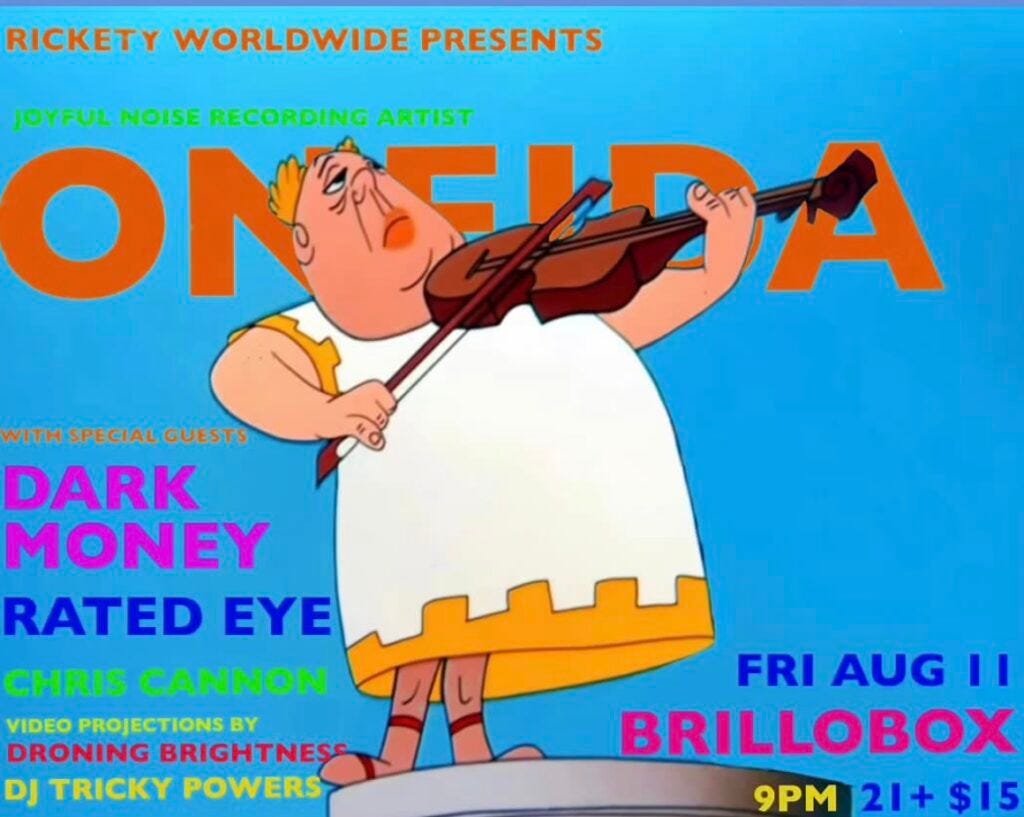

Thanks to a case of Covid, Oneida ended up missing last summer’s Pittsburgh gig. This Friday, August 11, they’re making good on their promise to reschedule. The show, at the Brillobox, celebrates their 25th anniversary of playing Pittsburgh, the dawn of the enduring Oneida/Rickety Records friendship.

Oneida X Rickety features performances by various members of the amorphous Pittsburgh-based art collective’s extended universe: Rickety founder/archivist Mike Bonello (DJ Tricky Powers) will be spinning some of the label’s greatest hits. Droning Brightness, new to the scene but not new to his craft, provides video projections. Chris Cannon, an OG DF member, performs, as does Rated Eye (featuring John Roman, who helped record DF’s unreleased demos), and Dark Money, featuring “T-Glitter” and long-time collaborator Eric Yeschke. Of Dark Money, Carroll says they’ve been “working hard to hone our dark chaotic ‘anti-groove’ (coined by a member of Dead Rider at Brillo a few years back) in one of our best suites yet!”

In the early '90s, a Pittsburgh band called Tiny Little Help moved to Albuquerque, where they lived in a storefront, played shows, and generally freaked out the locals with their wild sounds and onstage antics. With that band’s first record, The Mad Leafless Tree, Rickety Records was born. When they eventually returned to Pittsburgh the members of Tiny Little Help propagated a handful of other bands, including one called Dead at 24, which Carroll — then a member of the Johnsons, a band that Colpitts describes as “A-MA-ZING” — happened to see one night at the Bloomfield Bridge Tavern. He felt an immediate kinship, and was soon hanging out at the so-called “Rickety House,” in Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood. Within a few months, the Dirty Faces had formed with Carroll as their charismatic and unpredictable frontman.

Colpitts remembers playing Rickety Thursday, a weekly show held at a grimy biker bar called the 31st Street Pub, which boasted three-band bills, dollar admission, and dollar tequila shots.

“We were blown away by the whole thing,” he recalls. “There wasn’t [another] place [on that tour] where we felt like the band and the people were coming from the same place as us.

“They were into, you know, Cleveland punk and Peter Laughner” – the inspiration for the name Dead at 24 – “and they were into the Wu Tang Clan, they were like, just ridiculous characters.” Seeing the Dirty Faces, he says, “it must have been an early show [on the tour] because we were like, if this is what we’re about to experience around this country, we’re gonna have a lot of learning to do. But it turned out they were like, the strongest band we played with.”

The friendship between the two bands was already established by the time McManigle found herself living at the Rickety house. Once, when Oneida was in town, she told Colpitts she was interested in taking up the drums.

“John said, ‘Oh sit down at my kit.’ And I kept time on his kit and he said, ‘See? You can play drums.’ And that’s how it started.” Carroll asked McManigle to join Bill Baxter as the Dirty Faces’ second drummer, and she learned to drum on the job.

Colpitts and co. continued to be the Dirty Faces’ biggest champions. When Oneida’s label, Jagjaguar, agreed to give the band their own imprint, they released the Dirty Faces’ first two records: Superamerican and Get Right With God.

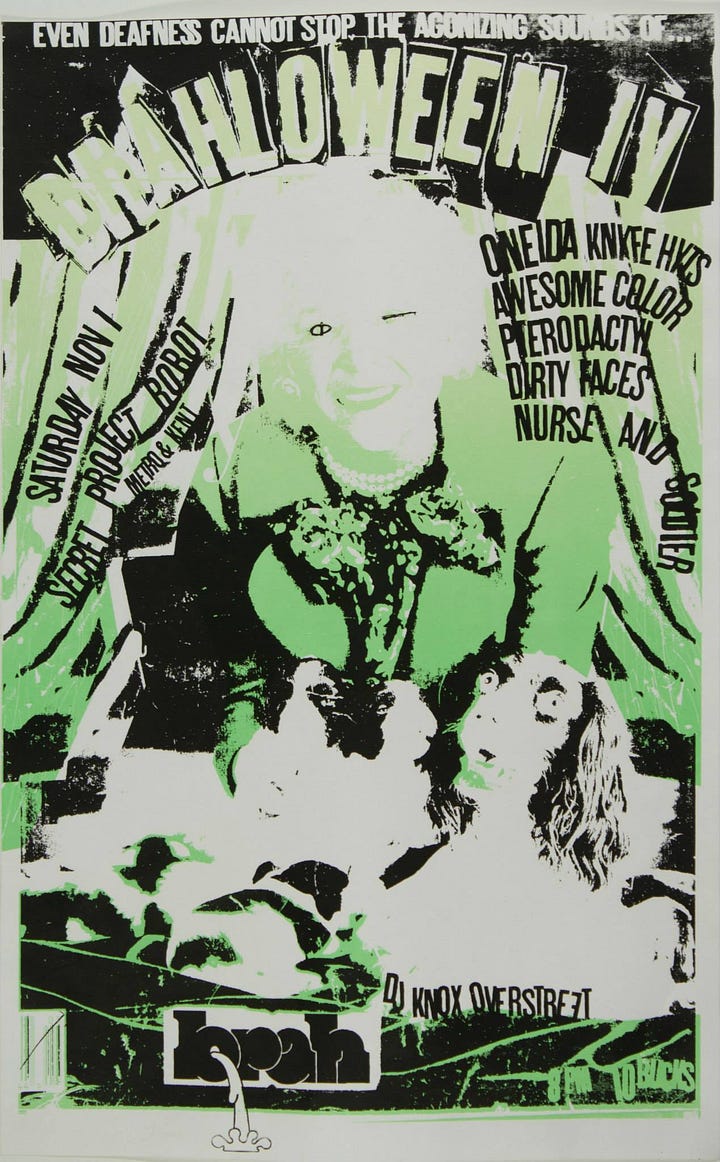

The imprint, Brah Records, put out a handful of other records for other bands: Parts and Labor, Pterodactyl, Nurse and Soldier (featuring Oneida’s Bobby Matador), Oakley Hall (featuring ex-Oneida member Pat “Papa Crazee” Sullivan). Though Colpitts admits that he had neither the business sense nor the time to run a profitable label, “it was a great thing,” he says. “It was cool, man. Jagjaguar did a lot for us. Until they couldn’t stand it anymore, you know what I mean? However many years of [it] just [being], like, so ridiculous. And to be honest, Dirty Faces were not easy. …Oh, God, some of the shows.”

He remembers one show in a Brooklyn loft where the Dirty Faces showed up six hours late, and Carroll – “I think he had just eaten a bag of circus peanuts or something” Colpitts laughs – spent the five-song performance lying on a couch. “But it was the most viscous, heart-wrenching, painful ecstatic show I'd ever seen,” he says, still amazed at the memory. “I get chills when I think about it.”

McManigle doesn't know which show that was exactly – it could have been a few, since wrangling band members was a constant challenge. Where Oneida has weathered the better part of three decades by being more functional, productive, and communicative than your average rock band, the Dirty Faces had a reputation for being chaotic, both onstage and off, thanks to a mix of intense personalities and varying levels of substance abuse problems. That was, of course, part of their appeal.

“I read something where Mike [Bonello] said, ‘It’s like a train wreck which is fun to watch when you’re outside it, but not quite as fun when you’re on the train.’ And that’s pretty apt.

“We fought all the time. We fought in practice, it wasn’t just onstage when there was an audience,” she says. “It was [seen as] a stage persona, but we were just being us, it wasn’t an act…. We were ramshackle madness, barely contained.”

They could be hit or miss, Colpitts says, “but when they hit it was so emotional. My experience of them was just this crazy emotion. I don’t know, the Stooges are like that too. And the technique, [guitarist] John Purse crossed with [guitarist] Julie Chill, John can play anything, but Julie was so rock solid.”

They were six very different people, “different on every level,” McManigle says. Just deciding what to listen to in the van was a nightmare, but they all loved Oneida.

In some ways the relationship between the two bands sounds like a rock ‘n’ roll Big Brothers/Big Sisters program, but the two bands were kindred spirits and, when it came down to it, equally matched in their potential powers. “Obviously we’re two different animals in a lot of ways,” McManigle says. But when the two bands toured together in 2008, she says, it was a shame that that tour wasn’t recorded every night. “Because whenever we played with Oneida it was like who's going to out-do who? Who’s going to do the better show here? …Generally they were the headliners, but we were like, ‘We’re going to make this really hard for you, you’re going to have to win this crowd back from us.’

“[Oneida] might be a little more polished and more professional, just the way that they do things, but they have the same vibe. They want to go out and have people give them a run for their money. They want to have people throwing it down, because they do every time they play. No matter how small the room or how empty it might be … they bring it the same way every time.”