Eric Wolfson on From Elvis in Memphis

“I feel like if Elvis had done a couple more maneuvers like that, he could have just thrown off the Colonel.”

In 2021 I interviewed Eric Wolfson about his contribution to the 33 1/3 book series, From Elvis in Memphis. This piece originally ran in the spring of 2021 in the Pittsburgh Current, a little upstart alt-weekly where I served for a couple years as music editor. The Current no longer exists in any form so I’m re-running that piece here.

I met Wolfson maybe 20 years ago in Pittsburgh. He had just graduated from Carnegie Mellon University and was working at a used CD store that I frequented. Not too much later he moved to Boston, and then to Brooklyn and then DC. We remained pen pals, and I continued to benefit from his considerable knowledge via mixtapes. I’d always been obsessed with music in a way that was hungry and chaotic. Wolfson, a natural historian, helped to (and continues to help) ground me in the larger historical framework that is still, in its own way, hungry and chaotic.

I asked Wolfson, who is currently working on a book about concept albums, if he was ok with the re-post. “By all means,” he said via text. “As a child of the '80s, I always wanted to be in re-runs.” I’m resisting the temptation to make any changes to the original version per Wolfson’s wishes: “I’m a history snob & believe in the ‘first draft of history’ being re-run (here we go I hate using this word yet here I am) authentically.”

From Elvis in Memphis is available for purchase here and they probably have it at your local bookstore.

In both casual cultural representation and informal memory, the life of Elvis Presley is often divided into two parts: Young, hip-shaking Hound Dog, and bloated, jumpsuit-wearing Vegas icon.

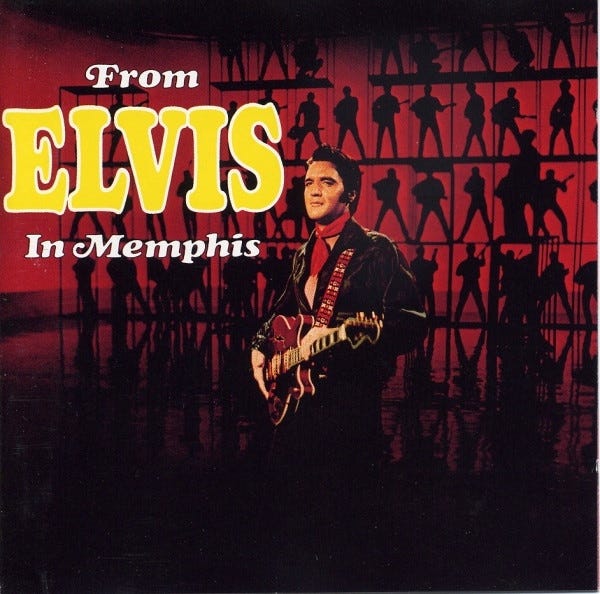

From Elvis in Memphis — Carnegie Mellon University alumnus Eric Wolfson’s 2020 contribution to the 33 ⅓ book series — explores a time in-between, when the King, if only temporarily, reclaimed relevance and musical power.

The Elvis of this book — an in-depth track-by-track study of the 1969 record From Elvis in Memphis — is an artist at an artistic and cultural crossroads. In just over 160 pages, Wolfson offers a compelling, slightly tragic and surprisingly full look at the ultimate larger-than-life artist.

Having spent most of the 1960s phoning in musical schlock and acting in cheesy Hollywood movies (and living more-or-less under the control of his manager “Colonel” Tom Parker), Presley was wildly out of step with the explosion of hippie culture and psychedelic rock happening in the culture at large.

By the late ’60s, Wolfson writes, Presley, then in his mid-30s, was “worse than dead — he was irrelevant,” and he knew it. It was time to make a move. Plans were put into motion for a live NBC comeback special, which would air in December of 1968. Against the wishes of the Colonel, who wanted a traditional Christmas program, variety show producer Steve Binder was hired to tweak Presley’s sound and image, and make something that would appeal to younger audiences.

One day, while Binder and Presley were driving down Sunset Boulevard, Binder asked what Presley thought would happen if he walked down the street unattended. Would he be mobbed? Presley didn’t know.

A few days later, as an experiment, the two men ventured out on their own. Binder recalled,

“We were both waiting for something to happen. Cars were driving by, not even bothering to look at us. No horns were honking, and no California girls were rolling down their windows to get a look at Elvis or scream his name. A couple of seedy looking hippies almost bumped into us as they were heavily engaged in their own conversation.

Binder allowed that, had the public been given a heads up, it would have been a different situation. As it was, most jaded Hollywood types would probably assume they were seeing a look-alike. But for just a moment, Wolfson writes, “[Presley] was reminded what it would be like to be nobody.”

The comeback special was a huge success. Like a man outrunning his own cultural demise, Presley gave one of the freest and liveliest performances of his career. Within months, he’d ride that energy back to his hometown of Memphis, Tenn., returning as a prodigal son looking to claim his inheritance.

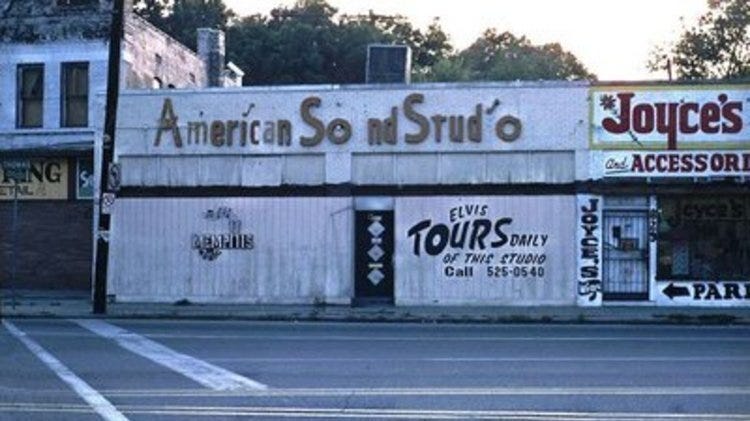

Defying the Colonel's plan to record at RCA, Presley chose Chips Moman’s American Sound Studios. Between opening in 1964 and closing in 1972, more than 100 hits including tracks by Wilson Pickett, Neil Diamond, Aretha Franklin and Dusty Springfield were recorded there. Part of what made American Sound special was the studio’s house band, The Memphis Boys, for whom Presley would be playing bandleader. After what Wolfson describes as “years recording filler tracks for generic films with faceless musicians,” working with a real, legit live band would be a change of pace for Presley.

“He was now ready to engage as a creative artist,” Wolfson writes. “For the first time in years, Elvis walked into a recording studio and acted like he cared.”

Wolfson was around 8 when he was given his first radio. He wanted to hear the Beatles, and asked his mom what station he should listen to. She directed him to the oldies station. “Which probably wasn’t the best answer because the oldies station — Oldies 103.3 in Boston — played about one Beatles song for every five Elvis songs. At the same time, 8-year-old me didn’t consider that I could change the channel,” he laughs. “So I basically got inundated with Elvis.”

By the time he was a teen, he’d visited Graceland and Sun Studios, the latter of which really knocked his socks off. Where Graceland felt like a museum, Sun Studios felt like a laboratory. “I loved the community of it, and the history,” Wolfson recalls. “The fact that that was the one room where everything happened, it just blew my mind.”

At CMU, Wolfson took a rock history class taught by Scott Sandage (author of Born Losers: A History of Failure in America) a course that would later be taken over by another colleague of Wolfson’s, Michael Witmore, who is now the director of the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC. (Wolfson also lives in DC, and works for the Library of Congress in the United States Copyright Office).

Both former professors have continued to support Wolfson’s work: Sandage, in particular, served as a sounding board for From Elvis in Memphis. “Part of why it reads so well, I would say, is because of his input,” Wolfson says.

From Elvis in Memphis is, somewhat stunningly, the first-ever volume to focus on one individual Elvis record. Wolfson digs deep into each song, exploring the personal and biographical motivations behind Presley’s selections, and examines the larger musical lineages, including stories about the songwriters themselves (Elvis famously didn’t write his own stuff) and similar songs from earlier eras. Moving forward and backward in time, he places Presley within a larger context of rock n roll specifically and American culture in general.

This record wasn’t Wolfson’s first choice: Before this, he’d already pitched several other ideas to 33 ⅓, none of which panned out. From Elvis in Memphis was, finally, “the best Elvis album that I hadn’t tried to pitch yet,” he laughs. But, “as I approached it, I realized that it was actually a good one for me, because it's really Elvis facing adulthood.

“Now that I'm, like Elvis, a grownup, and have kids and stuff, it's interesting to hear it as more of a mature statement as opposed to him being young and sexy and footloose and fancy free,” Wolfson says. “I love that it’s a homecoming album, I love that it works in terms of his own career’s narrative. This is a literal comeback, this cashing in on the blank check that was the success of the TV special.”

In working with the Memphis Boys, Presley not only engaged with real, skilled musicians, but — for the first time in years, and maybe for the last time in his life —he received pushback from the people he was working with.

He arrived at American Sound with his own posse of producers, engineers and friends, some protecting the Colonel's interests and all ready to do his bidding. As Wayne Jackson of the Memphis Horns recalls, Presley’s entourage all tried to talk to him at once, “and we were tryin’ to get a job done. ...All they wanted to do was entertain Elvis.” There were too many people in the studio, Moman said, “and it was aggravating, I guess, on all sides.

“But I think they were kind of shocked when I stood up to them. They probably had never had anyone ask them to leave the studio before — but I did and it turned out better for Elvis.”

Therein lurks the ultimate tragedy of From Elvis in Memphis. “He does this comeback special, defying the Colonel and then the Colonel is, behind the scenes, getting all this stuff set up for Vegas,” says Wolfson. “And that basically puts Elvis back under his thumb, you could argue.

“I feel like if Elvis had done a couple more maneuvers like that, he could have just thrown off the Colonel.”

After this record, Elvis would never again set foot in American Sound. “He never made as good an album again. And he basically went back to doing schlock,” Wolfson says. “[He] just kind of went nowhere again. And just as he spent the '60s being kind of coddled by Hollywood, he kind of gets coddled again by Vegas and his never-ending tours.”

In his 1975 book Mystery Train, music critic Greil Marcus describes Elvis as “a supreme figure in American life, one whose presence, no matter how banal or predictable, brooks no real comparison.”

The problem with discussing Elvis is that, well, he’s Elvis. In addition to (among other things) the looming racial baggage (addressed early on in this book), there’s an inescapability to this “supreme figure” that can render him almost invisible. The visual signifiers of Elvis are as meaningful (or meaningless) as the man they signify.

Wolfson mentions, for example, an episode of Paw Patrol, of which his young son is a fan. “There’s a Halloween episode, and one of them is a superhero, one of them is like a pirate or whatever, and one of them is Elvis,” he says. “And they never say, like, oh you’re dressed up as Elvis. He just has the hair, he has everything. It's like the Munch Scream being an emoji.”

Given that, Wolfson says, “some of the feedback that’s made me the happiest from the people that like the book were that, they sympathized with Elvis and they’d never think of him as someone to sympathize with either because he’s Mr. Cool, or they didn’t think anything at all, or they thought he was kind of a jackass. And all those things are true. So it’s kind of a question of how you slice it.”