I have mixed feelings about year-end lists. Years ago, when my relationship with music journalism was different, I took them pretty seriously, and cared about whether or not I thought the top-ten rankings of various major outlets were “correct.” I still read them because I cannot resist anything that is presented in a list format, no matter how stupid or infuriating it is. It’s interesting to see what good stuff I’ve missed (and there is a lot of it!) and what mediocre artists have scammed their way into the rankings (just my opinion!)

There were actually a lot of records I liked this year, a few of which I’ve written about already (Bill Nace, Bill Orcutt, Oneida, Jenny Hval), but there’s too much too keep up with and at this point I don’t really care to try.

So here’s a list of ten things — records, books, perfumes, movies, etc. — that I enjoyed for the first time (more or less) in 2022. A few of these things were released in 2022, but most of them weren’t. Obviously it’s arbitrary and incomplete, especially since I can’t seem to remember anything before May. I’m going to start taking Ginkgo biloba in 2023. I can’t say 2022 was the greatest year of my life, but it is healthy, I think, to occasionally reflect on the things, old and new, that continue to make life worth living.

Andy Shauf

I always kind of dread Spotify Wrapped, in part because I’m mildly ashamed of how much I use it (159,497 minutes in 2022) and because I spend a lot of time listening to music that I don’t particularly like, or wouldn’t be listening to if I didn’t have to write about it. That is to say I don’t feel particularly “seen” by the cold, hard data. In terms of raw numbers, sure, I guess it makes sense that Classical Performance was my most listened-to genre, but it doesn’t make emotional sense because most of those classical performances were playing while I was asleep.

Having Andy Shauf as my top artist does make emotional sense. I’ve been a fan since The Party crossed my desk in 2016 (one of the last physical promo CDs I would ever receive). I spoke with him about that record for Pittsburgh City Paper, and joined basically everyone else who has ever written about him in hailing him as an exceptional storyteller, comparing him to idiosyncratically literate, introspective, funny singer-songwriters like Paul Simon or, more tonally speaking, Carol King.

When he was writing The Party he’d been reading short stories by Denis Johnson and Raymond Carver, and his songs tend to focus on small-looking, big-feeling, one-on-one interactions.

“Besides parties being something that you go to to have fun and let loose, I think in those scenarios people are a little bit more willing to give up more of their personalities than in other settings,” Shauf told me in 2017. “That’s kind of where you get to know people, and people show their true colors and true feeling whether they want to or not. … I guess I’m interested in that kind of thing: what people are really like.”

Wilds, his most recent full-length, came out as a surprise release in late 2021, not 2022, but as far as I’m concerned this is a 2022 record. I like it a bit more more than 2020’s lusher The Neon Skyline (itself a very good, if slightly uneven record), but the two releases are linked by a woman named Judy, who moves in and out of the protagonist’s life, sometimes as a memory ( “I only miss her when the skies are above” he melodramatically admits, at her introduction) – sometimes as a flesh-and-blood presence. On Wilds we find them (Judy and the protagonist, whoever he is) sitting at the bar, week after week, waiting for the evening lottery numbers.

The Neon Skyline is a concept album, a collection of vignettes from a neighborhood watering hole, and contains some of Shauf’s most focused story-telling, which he brings to life with odd, memorable melodies: “Living Room,” one of that record’s best tracks, is a snippet of conversation between acquaintances: While waiting for her drink a women overshares about disappointing her young son. “I mean, how fucking hard is it/to give a shit?” she asks bluntly, horrified and heart-broken at her banal failings. Her audience squirms.

Shauf meant for Wilds to be a sequel to The Neon Skyline, then narrowed the focus of the record from the barflies in general to Judy specifically, but that narrative didn’t quite work either. He’s said he never got to the heart of the story he was telling with Wilds — which is technically a collection of demos, though you’d never know it — but it doesn’t matter too much. The looseness feels like an accurate expression of the nature of memory.

“It was informed by trying to be really plain-spoken about mundane events that happen to people,” Shauf said in 2021, “that feeling of your relationships falling apart. It’s not a huge explosion. It’s just kind of piece by piece.”

Ellen Arkbro & Johan Graden

Ellen Arkbro and Johan Graden’s I get along without you very well wasn’t in my Spotify top five, but that’s only because it came out in September. I’ve listened to it almost non-stop over the last three months.

I was first seduced by the title. There’s no rendition of that standard here, but the suggestion of it sets the tone perfectly: Elegant, restrained, melancholic, intimate. Composer Arkbro and multi-instrumentalist Graden are each well-regarded in their respective experimental/contemporary classical music scenes, and though this record was born from a series of improvisational sessions, it is the last thing I personally expected it to be, which is a pop record.

There are chilly shadows of Chet Baker and warmer hints of Robert Wyatt, but those comparisons are incidental, and these modern torch songs are as beautiful and heartrending as any I’ve ever heard. Jennifer Kelly put it well in her review for Dusted:

It is easy to get fixated on what makes the sound of this album so unusual—the sense of space and quiet, the subtle merger of timbres, the introspective clarity of its wandering melodies—but that leaves out the important part. These are serene and lovely songs made of disparate parts that join effortlessly together. When you listen, you go to a different place.

Rabbit Year Kitchen

This relatively new monthly recipe Patreon is so delightful I just had to include it. The fancy-ish, seasonally-based recipes are accessible for a medium-skill cook like myself, and the entire aesthetic is darling. Sadly I missed out on ordering a paper copy of proprietor Melanie’s Rabbit Year Holiday Kitchen zine, but fortunately Patreon subscribers received a PDF copy and I’m planning to make the the Sticky Toffee Pudding and the Saigon Nog this week.

Akro Ink

I’m a sucker for olfactory tricks and to my nose this one is pretty nuts. The strange accord – like a musical chord, perfumers combine several notes to create a particular effect – is that of *getting* a tattoo: you smell the ink, yes, but also the bracing rubbing alcohol, the rubber gloves … and is that a hint of plasma? The Akro perfume line, created by Master Perfumer Olivier Cresp (the creator of Mugler’s groundbreaking blockbuster Angel), is intended to stir fond memories of naughty behavior (boozing, smoking, etc) and this one promises to take you back to your first time under the needle.

With a little time your nose starts to take apart the pieces that build the illusion: Vetiver, birch and a little bit of jasmine.

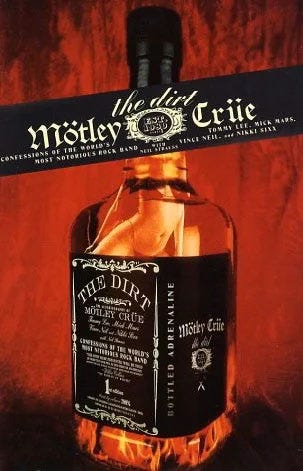

The Dirt: Confessions of the World’s Most Notorious Rock Band

This book – a first-person oral history of Mötley Crüe released in 2002 – probably needs no introduction. Even if you missed the book, by now a rock history classic, it’s likely that Netflix tried to get you to watch the movie version, which came out in 2019.

When I was a teenager I found a used copy of 1994’s Mötley Crüe ( the one they released with John Corabi replacing Vince Neil) the $2.50 section of my local used CD store. Obviously there’s no worse place to start with Mötley Crüe, but I didn’t know any better. I probably listened to it once and, while I think I have a copy of Girls Girls Girls kicking around somewhere, I never found the band particularly interesting. But I did sort of enjoy Pam & Tommy, which put me in the mood to learn more.

And, wow, I learned a lot! As advertised, the first half of The Dirt contains some of the most rotten shit I’ve ever read, so grotesque in its accounts of the band’s substance abuse, violence, misogyny and general vile behavior that on a couple of occasions I nearly abandoned it.

But it turns out that all this debauchery is going somewhere. Just as the reader (me) is getting sick of reading about groupies, Neil is getting tired of fucking them, and Sixx is too strung out to notice them or anyone else. The more things fall apart, the better the book gets. Neil and Mick Mars fret about how fat they’re getting from drinking (relatable). While Neil, Lee and Sixx cry about their childhoods in group therapy, Mars rolls his eyes and quits drinking cold turkey, using his own unique methods:

Whenever I craved a drink or felt frustrated I’d just curl my fingers into a circle as if I were holding a shot glass, yell “boom,” and snap my hand toward my mouth, as if I was hammering a shot of tequila. That was my boom, my therapy. I think it scared a lot of people but it made me happy. It was also a lot cheaper than rehab.

The Mick Mars chapters are the best parts of the book. In an AV Club review, Nathan Rabin wrote,

Mars genuinely seems to be on a different, much sadder, and more painful planet than everyone else. Physically, psychologically, and professionally, Mars has it rough, with a brain full of bad chemicals and a body riddled with arthritis. It’s hard to feel sorry for a millionaire rock-star alcoholic, but Mars ultimately emerges as a tragic and often pathetic figure.

Tragic and pathetic, sure, but Mars’ relative stability and disinterest in the toddler-level terrorism of his bandmates comes as a relief.

The Netflix movie was badly reviewed and it is pretty terrible. On a purely narrative level it is very confusing. If I hadn’t read the book I’d probably have no idea what was going on, and for better or worse it doesn’t convey the psychotic and often criminal behavior of the band, nor does it capture the very real suffering endured by the members later on. As a longtime Vince Neil hater, reading about the freak illness and death of his young daughter made me wonder if perhaps karma was going overboard in settling the cosmic score.

It is, however surprisingly well-cast: I particularly enjoyed MGK as Tommy Lee — the two share the same moronic puppy vibe — and The Righteous Gemstones’ Tony Cavalero as brain-damaged gross-out king Ozzy Osborne.

Rogue Perfumery

A few months ago I scored a gently-used bottle of the now-discontinued Flos Mortis, a camphorus tuberose scent. The “juice” is a gorgeous orange red, and smells, at first spray, like cough drops and Dimetapp before settling into a heady, wilting white floral suitable for a funeral parlor. I love it! I’m already sad about someday running out.

I can understand why others might find this fragrance challenging. Fortunately, Rogue — founded in 2017 by Manuel Cross — has a number of more “wearable” scents, which all share a certain vintage sensibility. They might share DNA with your grandmother’s favorite perfume, but they’re very modern and might even serve as a gateway to appreciating (or replacing) some of the more alienating or watered down or hard-to-find classics. I got myself the discovery set (a great deal, btw, IMO, lots of bang for your buck) and once I have a little more money I’m getting myself a bottle of Rostracto, a woody, spicy, strangely dusty rose scent.

Emmalea Russo/Cosmic Edges

The best way to give the impression of being smart and with-it is to steal ideas from someone who is smarter and more with-it than you are. This is why I subscribe to Emmalea Russo’s Substack, Cosmic Edges. The Jersey shore-based poet first caught my attention as a reoccurring guest on Barrett Avner’s freeform conversational podcast Contain, which I listened to a lot this summer while I was packing to move. Russo talked about Simone Weil and Byung-Chul Han and modernity and mysticism, and about her fixation with light, particularly cinematic light, especially the use of light in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which she writes about in her 2022 collection of poetry, Confetti. I’m not a big reader of poetry, and much prefer Russo’s prose, where she makes poetry, as a concept, into something I can’t help but love. (At that point I return to her poetry, which is mostly not for me. That’s how it goes with poetry, I guess).

Russo is a connoisseur of Weil’s sickest burns, which alone makes Cosmic Edges worth the price of admission ($5/mo), but she’s also prolific and sensible and funny and adept at joining the extramundane with the earthly.

Vengeance is Mine

When I think of Michael Roemer’s Vengeance is Mine, which is pretty often, what I first remember is the general *feeling* of it, and then how it looked.

I was just a few months old when it was released in 1984 and the women dress the way my mom is dressed in old family photos. In one scene, a young couple sits at a piano singing “Who Will Buy” from the musical Oliver, one of my first favorite movies. Not everyone will find these details as stirring as I did of course— I’d guess most people feel a certain attachment to media from the time of their birth — but I’d wager that Vengeance is Mine has the power to entrance viewers both much older and much younger than me.

As I heard one man observe in the movie theater lobby this summer, Vengeance is Mine is a bit like “three movies in one,” but even that description suggests a kind of structure that isn’t necessarily so clear cut. It opens with a close-up of Jo (Brooke Adams) on an airplane. She is very tense, her adoptive mother, who never really liked her, is dying, and Jo is on her way home to tie up emotional loose ends. But this is not the family drama in which we become ensnared. Jo befriends a preteen neighbor, Jackie, whose parents are in the middle of a contentious separation. Jackie’s unsuccessful artist mother, Donna (Trish Van Devere) eagerly takes Jo on as a friend and confidant. It seems for awhile to be a story of female suffering and solidarity turns into a horror story as Donna’s instability becomes increasingly evident. But it’s more complicated than that, and Van Devere’s performance in particular is sublime.

Vengeance is Mine never enjoyed a theatrical release, instead it was aired on PBS’s American Playhouse with the title Haunted. Pretty unfair considering what an exquisite work of art it is, but it’s strange pacing would, I imagine, fit perfectly with the sorts of things I remember my parents watching on public television at a time when public television was much better funded.

This past summer Film Forum gave the movie it’s long-overdue big screen release. In a rather rave review for the New York Times Wesley Morris wrote,

…what you’ll witness is an American movie executed with a French film’s interpersonal insouciance. It still feels original, in other words — one of those movies that somebody wrote and directed (Roemer, in this case) but that feels controlled entirely, engrossingly by human impulse, lawless in its way.

If you’re adept at illegally downloading movies (I’m not) you may be able to track this down, otherwise it’s a bit hard to stream. Keep an eye out for it at a repertory theater near you. Sadly I will miss the encore showing at Film Forum featuring a Q&A with Adams and Roemer, but if you’re in the area I highly recommend attending.

Dev Murphy’s perfume oils

My friend Dev Murphy is a triple (at least!) threat, a talented writer, visual artist and now perfumer. Last Christmas she gave me a rollerball of her first creation, Tiny Bed, a warm and spicy jasmine/clove scent that strikes me as both original and nostalgic in a way I can’t quite put my finger on. She’s expanded her line since then and my favorite is Staircase, a musky rose vanilla with a hint of pepper and lemon that makes it jammy and delectable. At this point I have a somewhat extensive perfume collection, but I reach for Staircase when I want to smell uncontroversially good, and I always get compliments.

Evan S. Connell

It really doesn’t get much better than Evan S. Connell’s 1959 novel Mrs. Bridge, a masterpiece of restrained storytelling. Through a series of 117 vignettes, Connell reveals the inner life of a repressed wife and mother of three who is seemingly unable to fully acknowledge the existence of inner lives, her own or anyone else's. It’s a book I’d like to buy by the case and hand out to everyone I know. We’re probably all close to someone like Mrs. Bridge, which is part of what makes this book so devastatingly indelible.

But! I read Mrs. Bridge in 2021 (thank you to Alana May Johnson for the introduction) so it doesn’t count. This year I read two more by Connell, The Connoisseur and Double Honeymoon. Written in 1974 and 1976, respectively, each follows the exploits of Muhlbach, a relatively button-down Manhattan-based insurance executive. In the first, a visit to New Mexico leaves him obsessed with the acquisition of genuine pre-Columbian art (he gets burned by some fakes, as any new collector might). In the second he becomes obsessed with a flakey, frustrating young woman who might just be out to burn him.

Neither of these novels are anywhere close to as effective as Mrs. Bridge, and The Connoisseur is superior to Double Honeymoon, but both are funny, insightful and a bit cruel (I still haven’t read enough Connell to know if the slightly hateful portrayal of a certain kind of women is Connell or Muhlbach, but for now I’ll give Connell, who died in 2013, the benefit of the doubt). In both, Muhlbach plays the straightman to a cast of characters who are, all told, only slightly more absurd than he is.

Connell is great at shining light on his protagonists’ blind spots, and Muhlbach’s own cranky or anxious or judgmental observations are often funny and/or true enough to warrant a dog-eared page. In Double Honeymoon, he’s suspicious of the counterculture represented by his wild younger love interest, and rightfully so, it seems. She’s doomed by her embrace of the “now,” just as Mrs. Bridge’s children are liberated by it. Ultimately Connell is curious and tender-hearted towards his characters, equally interested in their hopes and their disappointments.

As Blake Bailey put it in Bookforum: even when writing tragedy, Connell “saw the poetry” of these difficult relationships, “those lovely, ordinary moments of communion with people you love without quite knowing why.” A recent profile in the New Yorker echoes this observation: “…a mythographer rather than a mythmaker, an artist and analyst of the telling detail. “It’s precisely his independence of mind, the clarity of his roving imagination, that makes Connell worth reading. In his life as in his prose, Connell was suspicious of coherence, and mistrustful of invention taking the place of observation.”